In 1891, Jerome K. Jerome wrote, “Whenever five or six English-speaking people meet round a fire on Christmas Eve, they start telling each other ghost stories,” and he was only saying what everyone already knew.

From December to January, newspapers and magazines used to overflow with stories set on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, all about ghost children luring babies outdoors to freeze to death in blizzards, men seeking shelter from blizzards and being attacked by disembodied bones, men sleeping in unused nurseries and being attacked by goblin babies, woman attacked by “deformed idiotic sons” of wealthy families, women attacked by their husbands’ identical twins, women attacked by vampires, women haunted by screaming faces that drive them insane, women cuddled all night by escaped lunatics which drives them insane, priests haunted by possessed clothes that slowly drive him insane, and doctors visited by decapitated lady ghosts who drive them insane. As the British Mental Health Foundation says “Christmas is a time of year that often puts extra stress on us, and can affect our mental health in lots of different ways.” Indeed.

The earliest published proto-Christmas ghost story appeared in Washington Irving’s The Sketch Book (1819), which contained essays praising traditional customs, parodying modern manners, and then a long series of Christmas essays describing vast country feasts that end with ghost stories around the fire. The Sketch Book then unveils its highlight, its own tale told round “the winter evening fire”—“The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.”

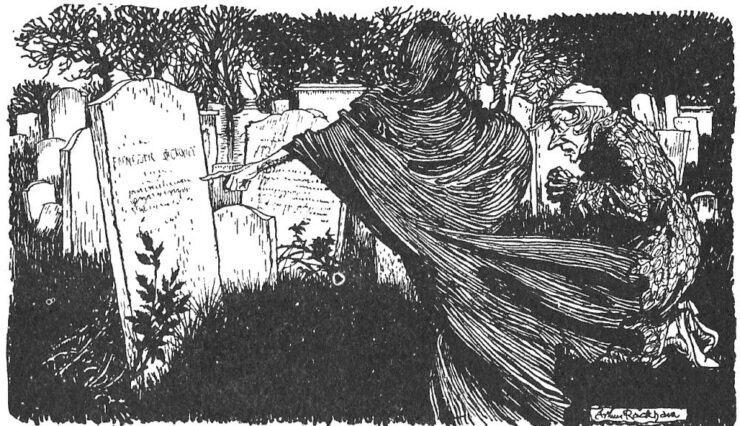

A few years later, British people, clearly feeling inferior, elected Sir Walter Scott, author of Ivanhoe, to level the playing field with his short story, “The Tapestried Chamber,” in 1828. It was wildly popular, and so a literary tradition was born. Which by 1860 was being roundly criticized. “WHAT is the matter with a large number of the Christmas story-tellers?” the Jersey Independent and Daily Telegraph lamented. “They seem to be labouring under an attack of the ‘dismals’! Instead of mirth-inspiring, side-shaking stories, they give us churchyard tales of broken promises, blighted hearts, blasted heaths, burglarious offences, brutal murders, and an occasional dash of ghostly visitations.”

The majority of Christmas ghost stories came in one of two flavors. One variety revolved around a grand house hosting a Christmas party with one too many guests. To accommodate them, the host has to open up the Disused Green Room, or The Abandoned Nursery, or The Dusty Attic and there the surplus visitor encounters something horrible that drives them insane. The other strain took place at a grand old country home, with a name like Ivy Lodge or Huntingfield Hall, where a drab and common visitor arrives and falls in love with a member of the great family who owns this historic pile, a family who traces their lineage back for hundreds of inbred years but now, oh woe, these modern times! The young lovers may not marry because these chinless gentry have been too stupid to manage their own finances and have fallen on hard times and Wolverdern Hall, or Gurthford Manor, or Dulverton Castle must be given up and soon unwashed plebes will tromp through its halls eating ice cream on their way to buy postcards at the gift shop. But then! As the gauche guest slumbers one night they are visited by the hideous phantom of some ancient ancestor who silently leads them to a secret passage revealing a hidden chamber containing a great treasure which allows the family to be rich again without having to debase itself by getting actual jobs and now the marriage can take place and some outsider DNA can finally be injected into their dusty old gene pool.

As Queen Victoria probably said, “As long as there are ghosts willing to lead social climbers to hidden chambers full of ancient jewels, the sun will never set on the British Empire.”

For most of us, however, there is only one Christmas ghost story, the only book to have been adapted by Bugs Bunny, the Flintstones, the Smurfs, the Muppets, the Real Ghostbusters, WKRP in Cincinnati, and the Slovakian National Opera, Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Clocking in at a brisk 30,000 words, Carol blends the spirits of the dead, joy to the world sentimentality, and poor people starving to death into a weapons-grade cocktail of yuletide delight.

A huge hit, Carol inspired a wave of parodies like “A Story of the Fantom Ass” in which a generous, kindly man is visited one Christmas by the spirit of a ghost donkey who shows him the evil impact his generosity has on those around him. When he awakens on Christmas morning he repents and vows to become a miser. In “The Subsequent Career of Marley’s Ghost” the ghost of Jacob Marley keeps making moral visits to different misers with diminishing returns. Worn familiar from overexposure, they disregard and ignore the phantasmal Marley until he ultimately goes insane and is committed to a mental asylum for ghosts.

Today, A Christmas Carol is like that ghost: overly familiar and easily ignored. But re-reading it, you realize Dickens’ evergreen tale achieves something few Christmas ghost stories actually ever managed: genuine grief. Written during the “Hungry Forties” when an economic slump followed by three years of bad harvests set off a global crisis that saw mass emigration and widespread famine, the Carol is haunted by true poverty, probably because Dickens was writing it while walking past starving parents cradling the emaciated corpses of their children in the street.

But more than that, Dickens understood the melancholy spirit of the holiday season. As he wrote almost a decade earlier in The Pickwick Papers, “Many of the hearts that throbbed so gaily then [in the Christmas gatherings of our earlier years], have ceased to beat; …the hands we grasped, have grown cold; the eyes we sought, have hid their lustre in the grave; and yet the old house, the room, the merry voices and smiling faces, the jest, the laugh, the most minute and trivial circumstance connected with those happy meetings, crowd upon our mind at each recurrence of the season, as if the last assemblage had been but yesterday. Happy, happy Christmas that can win us back to the delusions of our childish days…”

Christmas is a time to be haunted by our memories, for every Christmas is our first Christmas without. That moment we pause while setting the table or addressing cards and think, “Oh, this is the first Christmas without Aunt Lee, without Uncle Gordon, without Pete, or Betty, or Erica,” or whoever it is we lost the year before.

To my mind, there is one other story that manages this feat. Stephen Leacock’s “Merry Christmas” appeared in Hearst’s Magazine in 1917, less than a month after World War I’s Third Battle of Ypres ended with 700,000 casualties. It begins on a self-referential note as a writer tries to write his Christmas story. He’s visited by Father Time who asks if he can invite in his friend, Father Christmas, who might provide inspiration. They open the door and there he stands, “All draggled with the mud and rain…as if no house had sheltered him these three years past. His old red jersey was tattered in a dozen places, his muffler frayed and raveled. The bundle of toys that he dragged with him seemed wet and worn till the cardboard boxes gaped asunder.”

Father Christmas is too scared to enter the house because it’s lit only by candles and he’s become frightened of the dark. He’s terrified the floor might be mined because he stepped on a mine in No Man’s Land between the trenches back in Christmas 1914 and it “broke his nerve.” He hallucinates a machine gun nest in the corner because, as Father Time explains, “They turned a machine gun on him in the street of Warsaw. He thinks he sees them everywhere since then.”

Father Christmas finally enters the house when a backfire from a passing car sends him into a panic. “Listen!” he screams. “It is guns—I hear them!” The writer reassures him it’s only a car. “Do you hear that?” Father Christmas says. “Voices crying?” The writer and Father Time reassure him that there are no voices crying but Father Christmas insists:

“My children’s voices! I hear them everywhere—they come to me on every wind—and I see them as I wander in the night and storm—my children—torn and dying in the trenches—beaten into the ground—I hear them crying from the hospitals—each one to me, still as I knew him once, a little child. Time! Time!” he cried, reaching out his arms. “Give me back my children!”

And so, in 1917, we reached the Christmas Number in which the living have become so monstrous they caused the actual supernatural spirit of Christmas to go insane.

Merry Christmas, everyone.

Here’s hoping your holidays contain all the horror and mayhem that tradition requires, and that one midnight a ghost appears in your dreams and leads you to a hidden room full of desiccated corpses and piles of lost gold.

Originally published December 2022.